The Ghost of Michael Jackson

In our first week of quarantine, Jason came up with a game for the boys. From Sam's detective kit, we had one of those pens that can only be read with a blacklight. Jason used it to write a note to Sam; that note had a clue as to where to find the next note, and so on and so forth, sending him on a scavenger hunt. Each note was taunting like the bad guy from a cartoon: "Think you're smart? You'll never figure out this next clue..." They were all signed, "Your Arch Nemesis."

Sam sank his teeth right into this scavenger hunt. Even though society was starting to lock down, it was technically the boys' spring break, so we ignored the emptying grocery shelves and parking lots and pretended we were on a voluntary staycation. This detective game helped us keep things light. Sam raced from room to room, trying to decipher the clues and find the next sheet of paper. By the time he had all five, he was breathless.

Henry followed quietly at Sam's heels, holding a stuffed bear to his chest so that the top of the bear's ears covered the corners Henry's mouth. Henry's brown eyes, bright and dark, were taking it all in. For hours after they were supposed to be asleep, Sam and Henry chattered over who this mysterious "arch nemesis" note-leaver could be. While the mystery filled Sam with adventure, it also caressed Henry with fear.

Our house had a ghost, Henry decided.

"What ghost?" Sam asked.

"The ghost of Michael Jackson," Henry solemnly replied.

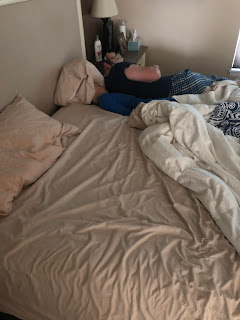

He seemed pretty sure...and pretty scared. While Henry typically sleeps heavily through the night, here's how he slept that night (he's the tiny guy in blue pajamas snuggled up against my husband):

While I have not personally felt the presence of Michael Jackson in our house, I have noticed this: As the forced solitude lengthens, my mind grows more crowded with ghosts. By "ghost" I mean a sort of spiritual dissonance--a heavy, formless presence from the past that I cannot reconcile with my present. Perhaps this is why, as I noticed in my brainstorming, that we tend to grow weaker, more vulnerable, and more preyed upon as we endure an aloneness we did not choose. Without the distractions of lunch packing and happy hours and swim lessons and group exercise and driving to work, I am visited by moments from the past that I do not care to be visited by.

There's a reason why gothic stories tend to have a nearly vacant house; the landscape, both internal and external, must be empty before a ghost a may enter. Or perhaps the ghost is always there, but we won't notice it if we're always rushing from one thing to the next. In Parasite, the man who lives in the secret underground bunker, along with the family who lives in the semi-basement, serve as their society's ghosts. They are remnants of a foul-smelling caste system ignored by anyone with enough privilege to turn their backs to it. Something I've noticed about ghosts in stories: they will not be ignored. Parasite is no exception here (if you haven't seen the movie and you plan to, don't read the rest of this paragraph). As the men of the basements storm the opulent birthday party of the wealthy family's little boy, it become clear that the repressed / the oppressed, just as in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart," can and will take the life from the repressors and oppressors before returning to the underworld of the banished.

One scene from the film that interested me in particular: The wealthy, naive mother tells a story about the time her little boy, Da-song saw a ghost. The little boy had snuck down to the kitchen in the middle of the night to eat more birthday cake, and he saw a "ghost" coming up the stairs. The filming of this scene is one of the more frightening moments in the movie. Here's the clip:

The dramatic irony is that we know who that figure is, and we know that he's a flesh-and-blood human. But we see this moment through Da-song's eyes: the ominous darkness at the top of the basement stairs, the ghoulish eyes and flesh...the gap between what is real and what is imagined closes here, which is what happens when an ignored, unwanted entity confronts us. This ghost-like man has been living in the bunker of a wealthy family's house for years without being noticed. I left the film thinking, what ghosts are lurking in our bunker? What have I--have we--built our busy lives upon without ever taking notice of?

Interestingly, this is also the moment in the film where I feel the most empathy for Da-song's mother, Yeon-kyo. The "ghost" that emerges from the stairwell is not just Da-song's monster under the bed, nor is it solely a symbol of an oppressed caste; in this flashback, it is also an embodiment of the worst trauma a mother can endure: watching helplessly as death tries to take your child. Tears fall down her smooth cheeks, choking her voice a bit as she tells the story of Da-song falling into a near-fatal seizure. In the filming, the cake appears on the floor before Da-song does, and Yeon-kyo remembers the cake in excruciating detail, right down to how the frosting tasted. This is how the ghost of a trauma often enters--through the small, seemingly innocuous details, like whipped frosting on a birthday cake. Then, if you're still enough, the ugly parts start to show themselves, too. When I think of Yeon-kyo in Parasite, she's always moving, just as most of us are--nearly jogging up the stairs, down the stairs, worrying about her son's behavior and her daughter's intelligence, hiring and firing people to keep up with the housework that she can't keep up with, planning a party, talking and talking. Although she's not alone in this scene, she's still and quiet; after a failed camping trip, she has nothing else to keep herself busy with, and so this memory returns to haunt her.

In quiet moments of this film, the "ghosts" reach out through flashbacks and Morse code, using blinking lights to connect the underworld to the living world. I think all traumas, all buried things from our past have a way of reaching out. With the quiet and stillness of solitude, I start to hear and see them.

My typical workouts (during non-quarantined life) are crowded and loud. I like to be surround by about 39 sweaty, middle aged people in the narrow, L-shaped studio at Highlands Ranch Orange Theory Fitness, my head filled with remixed hip hop and nonstop microphoned coaching. There is nothing but reps and survival. Everything else is pounded out.

Bu the gyms are closed now, so I have turned to quiet, solitary runs. On my run yesterday, a helicopter was circling a nearby neighborhood. Helicopters sound like wasps beating near my ears. Just like Baby Suggs hears the sound of hummingbirds as Sethe picks up the axe in the shed, I hear helicopters when my anxiety picks up. I think my brain performs this trick for two reasons:

1. After Sam had his first open-heart surgery when he was five days old, we stayed on the top floor of Children's Hospital for three months. We were close to the helicopter landing pad, and sometimes I saw children being rushed off the helicopter and into surgery. Something about the way helicopters hover, and paramedics jog, and slouched mothers follow with their hands over their faces...it's not quite human. It's something less. It's nothing I'd like to see again.

2. When the school shooting happened, helicopters descended like a plague of insects. They weren't there to rescue anyone, like the Children's Hospital helicopters. They were there to get the best camera angle on SWAT team officers gesturing with arms and guns, teenagers running out of their shoes with hands on their heads, flashing sirens turning the perimeter air red...The helicopter blades punched the air with the heavy rhythm of machine guns.

So, I don't like helicopters.

But right there, in the quiet blue sky of my solitary run yesterday, was a helicopter. And as my feet pounded the ground, the ghosts found their way in. For the next 45 minutes, I heard my jagged breathing and the beeping of newborn Sam's ventilator. I saw walkers peering at me over homemade masks and SWAT gear staring at me through the narrow, vertical window next to the English office door. Every footstep forward was loaded with the past. And I kept going.

At some point, I was running towards something instead of away from something.

By the end of my run, I actually felt pretty good. Exhilarated, even. Maybe this is what people who do yoga mean when they talk about meditating? I'm not sure, but I was glad to have a little time with these ghosts. I don't want to be like Jay Gatsby who fails reconcile his past with his present (I really want to include a quotation from the last page but am refraining for the sake of the book club reading Gatsby right now). I don't want to die like Baby Suggs, who could handle only the patchwork squares of color in her quilt because the spite of the past had claimed ownership of her present. I want to feel more like Denver, who in stepping back onto a road that had hurt her, discovered, "...."

In my initial brainstorming, I thought that forced solitude created spiritual dissonance. But after writing this, I think now that forced solitude invites you to recognize the spiritual dissonance--or the "ghost"--that was always there. In the solitude, our ghosts are sending us Morse code from the basement, and flapping swiftly near our ears. It's both exhilarating and scary (think: Sam rushing up and down the stairs laughing, Henry trailing stiffly with a teddy bear half-covering his face).

Solitude doesn't create ghosts; it just offers them a wall to cast a silhouette onto, or a creaky floorboard to step across.

Sam sank his teeth right into this scavenger hunt. Even though society was starting to lock down, it was technically the boys' spring break, so we ignored the emptying grocery shelves and parking lots and pretended we were on a voluntary staycation. This detective game helped us keep things light. Sam raced from room to room, trying to decipher the clues and find the next sheet of paper. By the time he had all five, he was breathless.

Henry followed quietly at Sam's heels, holding a stuffed bear to his chest so that the top of the bear's ears covered the corners Henry's mouth. Henry's brown eyes, bright and dark, were taking it all in. For hours after they were supposed to be asleep, Sam and Henry chattered over who this mysterious "arch nemesis" note-leaver could be. While the mystery filled Sam with adventure, it also caressed Henry with fear.

Our house had a ghost, Henry decided.

"What ghost?" Sam asked.

"The ghost of Michael Jackson," Henry solemnly replied.

He seemed pretty sure...and pretty scared. While Henry typically sleeps heavily through the night, here's how he slept that night (he's the tiny guy in blue pajamas snuggled up against my husband):

While I have not personally felt the presence of Michael Jackson in our house, I have noticed this: As the forced solitude lengthens, my mind grows more crowded with ghosts. By "ghost" I mean a sort of spiritual dissonance--a heavy, formless presence from the past that I cannot reconcile with my present. Perhaps this is why, as I noticed in my brainstorming, that we tend to grow weaker, more vulnerable, and more preyed upon as we endure an aloneness we did not choose. Without the distractions of lunch packing and happy hours and swim lessons and group exercise and driving to work, I am visited by moments from the past that I do not care to be visited by.

There's a reason why gothic stories tend to have a nearly vacant house; the landscape, both internal and external, must be empty before a ghost a may enter. Or perhaps the ghost is always there, but we won't notice it if we're always rushing from one thing to the next. In Parasite, the man who lives in the secret underground bunker, along with the family who lives in the semi-basement, serve as their society's ghosts. They are remnants of a foul-smelling caste system ignored by anyone with enough privilege to turn their backs to it. Something I've noticed about ghosts in stories: they will not be ignored. Parasite is no exception here (if you haven't seen the movie and you plan to, don't read the rest of this paragraph). As the men of the basements storm the opulent birthday party of the wealthy family's little boy, it become clear that the repressed / the oppressed, just as in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart," can and will take the life from the repressors and oppressors before returning to the underworld of the banished.

One scene from the film that interested me in particular: The wealthy, naive mother tells a story about the time her little boy, Da-song saw a ghost. The little boy had snuck down to the kitchen in the middle of the night to eat more birthday cake, and he saw a "ghost" coming up the stairs. The filming of this scene is one of the more frightening moments in the movie. Here's the clip:

Interestingly, this is also the moment in the film where I feel the most empathy for Da-song's mother, Yeon-kyo. The "ghost" that emerges from the stairwell is not just Da-song's monster under the bed, nor is it solely a symbol of an oppressed caste; in this flashback, it is also an embodiment of the worst trauma a mother can endure: watching helplessly as death tries to take your child. Tears fall down her smooth cheeks, choking her voice a bit as she tells the story of Da-song falling into a near-fatal seizure. In the filming, the cake appears on the floor before Da-song does, and Yeon-kyo remembers the cake in excruciating detail, right down to how the frosting tasted. This is how the ghost of a trauma often enters--through the small, seemingly innocuous details, like whipped frosting on a birthday cake. Then, if you're still enough, the ugly parts start to show themselves, too. When I think of Yeon-kyo in Parasite, she's always moving, just as most of us are--nearly jogging up the stairs, down the stairs, worrying about her son's behavior and her daughter's intelligence, hiring and firing people to keep up with the housework that she can't keep up with, planning a party, talking and talking. Although she's not alone in this scene, she's still and quiet; after a failed camping trip, she has nothing else to keep herself busy with, and so this memory returns to haunt her.

In quiet moments of this film, the "ghosts" reach out through flashbacks and Morse code, using blinking lights to connect the underworld to the living world. I think all traumas, all buried things from our past have a way of reaching out. With the quiet and stillness of solitude, I start to hear and see them.

My typical workouts (during non-quarantined life) are crowded and loud. I like to be surround by about 39 sweaty, middle aged people in the narrow, L-shaped studio at Highlands Ranch Orange Theory Fitness, my head filled with remixed hip hop and nonstop microphoned coaching. There is nothing but reps and survival. Everything else is pounded out.

Bu the gyms are closed now, so I have turned to quiet, solitary runs. On my run yesterday, a helicopter was circling a nearby neighborhood. Helicopters sound like wasps beating near my ears. Just like Baby Suggs hears the sound of hummingbirds as Sethe picks up the axe in the shed, I hear helicopters when my anxiety picks up. I think my brain performs this trick for two reasons:

1. After Sam had his first open-heart surgery when he was five days old, we stayed on the top floor of Children's Hospital for three months. We were close to the helicopter landing pad, and sometimes I saw children being rushed off the helicopter and into surgery. Something about the way helicopters hover, and paramedics jog, and slouched mothers follow with their hands over their faces...it's not quite human. It's something less. It's nothing I'd like to see again.

2. When the school shooting happened, helicopters descended like a plague of insects. They weren't there to rescue anyone, like the Children's Hospital helicopters. They were there to get the best camera angle on SWAT team officers gesturing with arms and guns, teenagers running out of their shoes with hands on their heads, flashing sirens turning the perimeter air red...The helicopter blades punched the air with the heavy rhythm of machine guns.

So, I don't like helicopters.

But right there, in the quiet blue sky of my solitary run yesterday, was a helicopter. And as my feet pounded the ground, the ghosts found their way in. For the next 45 minutes, I heard my jagged breathing and the beeping of newborn Sam's ventilator. I saw walkers peering at me over homemade masks and SWAT gear staring at me through the narrow, vertical window next to the English office door. Every footstep forward was loaded with the past. And I kept going.

At some point, I was running towards something instead of away from something.

By the end of my run, I actually felt pretty good. Exhilarated, even. Maybe this is what people who do yoga mean when they talk about meditating? I'm not sure, but I was glad to have a little time with these ghosts. I don't want to be like Jay Gatsby who fails reconcile his past with his present (I really want to include a quotation from the last page but am refraining for the sake of the book club reading Gatsby right now). I don't want to die like Baby Suggs, who could handle only the patchwork squares of color in her quilt because the spite of the past had claimed ownership of her present. I want to feel more like Denver, who in stepping back onto a road that had hurt her, discovered, "...."

In my initial brainstorming, I thought that forced solitude created spiritual dissonance. But after writing this, I think now that forced solitude invites you to recognize the spiritual dissonance--or the "ghost"--that was always there. In the solitude, our ghosts are sending us Morse code from the basement, and flapping swiftly near our ears. It's both exhilarating and scary (think: Sam rushing up and down the stairs laughing, Henry trailing stiffly with a teddy bear half-covering his face).

Solitude doesn't create ghosts; it just offers them a wall to cast a silhouette onto, or a creaky floorboard to step across.

I love your analysis of memory and ghosts! The employment of Parasite is great too. I never thought about the mother or the cake that way!

ReplyDelete